|

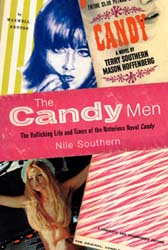

The Rollicking Life and Times of the Notorious Novel Candy |

|

EXCERPTS:

| Introduction When I was in grade school in 1967,

one of my six-year-old classmates, Daisy Friedman (now a writer), turned

to me and said, “Your father is a dirty old man!” I asked

how she knew that, and she said, “He wrote a book called Candy

— and it’s a dirty, dirty book!” Again, I

asked how she knew all this, and she said, “Because my parents

told me — they have it on their bookshelf.” Not knowing what

a “dirty old man” was, I came away with the impression that

whatever my father was, he was a great Upsetter. I would later learn

that young, literate New Yorkers had no issue about having a copy of

Candy in their libraries, but this was certainly not the case

across the country — censorship and prudishness were in fact still

alive and well, not only in the United States but abroad. I first got the idea for The Candy Men after reading a letter in Terry’s files from a British barrister advising how (even in 1968) the only way Candy could appear in England would be to undergo a “pornectomy” — eliminating about eighty instances of what was considered “indecency,” which the barrister had handily indexed in a kind of blueprint for the operation. The assessment featured page after page of cryptic references to offending words and passages to be excised or modified: Page 60 line 7 “COME” amend to “come to you” without capitals; Line 15 “jack-off” amend to “liberate”; Page 93 line 2 “exactly like an erection.” Delete. The legal advice appeared to me to be a kind of alchemical prescription for transforming the lively into the dead. I imagined the shoddy, disjunctive product such a procedure would have created — the spontaneous, irresistibly effervescent Candy Christian, her thoughts, feelings, and train wrecks of sexual experience becoming a clerical series of truncations and awkward politesse. She would be disfigured for eternity — or at least, ironically, for the British reading public — only because of the arbitrary mores and laws of the day, now long gone. By the 1980s, I understood that Terry’s friend Lenny Bruce had essentially died so that (at best) George Carlin and (at worst) Andrew Dice Clay could say “cocksucker” on HBO — and that the road to where we are now (i.e., anything goes) is paved not only with breakthrough books, but with broken lives. There were three men responsible for bringing the erotic fantasy Candy to fruition — and they could not have been more different. |

|

|

The first, Maurice Girodias,

was Europe’s most infamous publisher and indefatigable survivalist.

Girodias put out otherwise unpublishable works of (mostly) erotic literature

in English when the English-speaking world needed them most: Lolita,

Naked Lunch, Henry Miller’s The Tropics, the Marquis de Sade. As

Girodias wrote of himself, “The connecting link is clear enough:

anything that shocks because it comes before its time, anything that

is liable to be banned by the censors because they cannot accept its

honesty.” Girodias was also a seasoned gambler. “A day out

of court is a day wasted,” he used to quip. |

|

Mason Hoffenberg,

the second of the three, was one of the smartest, hippest, most undisciplined

poets on the scene — whether it be Joe’s Dinette, the Riviera

bar in the Village, or the Old Navy on the Left Bank of Paris. A “permanently

kicking junkie” as William Burroughs once described him, Mason

the writer never really got started — though Terry, his best friend,

described him as a “Nobel Prize–type genius.” |

|

And Terry Southern, a writer with a destiny and a killer ear for dialogue. Terry’s mandate was to take things as far out as they could go — with absolute credibility. A prose stylist gone Hollywood — his Texan, Irish, and Native American roots made him Trickster and Taurus bull — oblivious to the rules of the Game. Growing up around Terry’s work in Canaan,

Connecticut, and later helping him organize his papers, I was often

struck by the fragile carbon-paper pages of correspondence preserved

in one of the few manila files he labeled himself with such headers

as “Grand Guy Hoffer,” “Candy Legal,” and “Gid.”

The letters within these files were written on white onionskin, sometimes

on blue one-piece aerograms — each typed manually and with great

care for language and punctuation. They were light as air, as international

mail was expensive, especially for writers. I noticed that a whole slew

of these letters were addressed to Terry as “Master Maxwell Kent”

and were sent from a joker who never signed his real name, using “Yolanda,”

“Leslie,” “Jessica,” or any name other than his

own: Mason Hoffenberg. Terry also kept carbon copies of many of the

letters he had sent to Mason, some dating back to the mid-1950s. The

letters were entertaining — about people, hipsters, junkies, chicks,

who was “balling” whom, and what the latest “news”

was. Some were written on a barge in the Hudson, others on West 11th

Street, others in Switzerland. Mason’s were from Paris, Spain,

and the Dordogne. I got the sense that Terry kept these letters as evidence

of a life he had consciously lived — before fame blurred what life

was all about. They both drew out the best in each other. With Terry, Mason explored his craft and artistic approach without embarrassment — as he does in a letter from 1957, offering a glimpse into his unique “methodology”: |

|

"I’ve gotten all set up to answer your recent letter and find that I’ve mislaid it. . . . I’ve just gone through all my papers — and I’ve got plenty — but it’s not with the clippings containing Chinese characters, not in the specimens, not in the aborted poems envelope, not in the noteworthy language phenomena specimens, or lists-of-groovy-words sheaf and not in the folder (thin) of poems in their “heavy” and definitive versions (where it couldn’t possibly have been forgotten — you know how insanely careful I am of what goes in there, and a letter of yours, no matter how welcome, cannot and does not pretend, for that matter, to meet the brutal standards I’ve set for myself for what gets in to that elite company)." Similarly, Mason enabled Terry to tap into his feelings — even if expressed through a feigned earnestness, as in a letter from the spring of 1957, when Terry lauds Mason’s “warmth, goodness and affection”: It is of course your possession in such abundance of those very qualities which has so sustained the very real and high esteem it has over the years been my pleasure to feel for you. And, if, in your past difficulty [with drugs], my clumsy good-intentions were of help to you — let it stand in simple testimony to . . . the power of true-love. Shortly after Terry died in 1995, Leon

Friedman, who was Maurice Girodias’s lawyer, sent me his entire

Candy file. The letters, organized chronologically, provided

snapshots of the growing misunderstandings, temper tantrums, paranoid

fixations, jealousies, dreams, and utter despair that each of these

men went through as they tried to regain control over their bestselling

book lost in a miasma of cloudy copyright. Many of these documents had

capital letters (A, B, C, etc.) written on them, vestiges of their use

as evidence in the Candy trials. When I phoned him, Leon explained,

somewhat apologetically, that he had been Girodias’s attorney during

the fight over Candy. I sensed that he felt a little ashamed

for having served “on the other side” but also wanted me to

know that these papers he had given me were an important part of literary

history — the keys not only to one of the grands scandales

of publishing but to these incredibly enigmatic figures themselves. |

|

|

Candy was arguably the first (if not the only) “dirty book” to take hold of mainstream America (and its bestseller list) for so long. As a kind of literary confection, it was lighter than Lolita and never took itself too seriously. After all, the book had been under siege for five years in France, yet had been celebrated in Greenwich Village as fun contraband. Whereas My Secret Life and other underground, “anonymous” sex odysseys immersed the reader in the wholesale transgression of Victorian puritanism, Candy was swinging with the Now. It sold millions of copies in the United States, from its release in May 1964 through the summer of 1965 and beyond. Another reason the book infected so many so quickly was because it was so widely available across the country. Printing Candy was like printing money — the pirates had smelled the festering copyright problem like a pack of wolves, and sold millions without having to account to any authors or agents. The wild success of Candy can

be attributed to America suddenly growing up after the relaxation

of the “decency laws” that had kept such works as Lady

Chatterley’s Lover, Howl, and Last Exit to Brooklyn from

sullying America’s Doris Day–hallucination of cheerful,

neutered perfection. The release and embrace of Candy in some ways

symbolized America’s heralding of its own sexual transformation:

out of the repressive Styx of (Eisenhower’s) sleepy Wisconsin

and into the happening hipness of (Ginsberg’s) Village. Sex and

humor were anathema to the Eisenhower era, and in “heavy combo,”

as Terry would say, they were its knockout punch. On the front lines

of thawing the ’50s ice was an army of adolescent readers —

male and female — who were consuming the book urgently with one

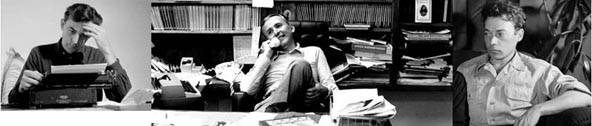

hand by night, and reading it aloud to the uninitiated by day. — N.S. Photos:

Maurice Girodias, by Gilles Lorrain, NYC, 1974. Mason Hoffenberg, Paris,

1956, Courtesy the Mason Hoffenberg Estate. |

|